03/04/2023 - 07/05/2023 / Week 1 - Week 5

Joey Lok Wai San / 0350857

Typography / Bachelor of Design (Hons) in Creative Media Task 1: Exercises 1 & 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

2. Instructions Task 1: Exercise 1 - Type Expression Task 1: Exercise 2 - Text Formatting

LECTURES

Lecture: Introduction

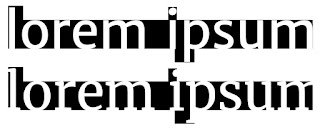

Font refers to individual font or weight within a typeface

E.g. Georgia Regular, Georgia Italic, Georgia Bold, etc.

Fig 1.1.1 Examples of Georgia fonts

Typeface refers to the various families that do not share characteristics.

Eg. Georgia, Arial, Helvetica, Times New Roman, Didot, Comic Sans, Futura, etc.

Fig 1.1.2 Examples of typefaces

Lecture 1: Development / Timeline

*Note: All or most information is taken from the perspective of the Western world which overlooks viewpoints from the rest of the world. Take all information with a pinch of salt.

It is important to contribute to the larger body of knowledge out there. The responsibility largely lies on student designers/researchers to give voice to the voiceless

1. Early letterform development: Phoenician to Roman

Writing initially involved scratching into wet clay or carving into stone with a chisel.

The uppercase letterforms were the only letterforms for nearly 2000 years. They are simple combinations of straight lines and pieces of circles.

Modern Latin and Early Arabic evolved from the Phoenician letters.

Fig 1.1.3 Evolution from Phoenician letter

Writing directions

Phoenicians: Right to left

Greeks: 'Boustrophedon’ (how the ox ploughs) - read alternately from right to left and left to right, and the same goes for the orientation of the letterforms.

Both Phoenicians and Greeks did not use letter space or punctuation.

Fig 1.1.4 Greek writing style, ‘boustrophedon’

Direction of letterforms

Etruscan and Roman carvers used to paint letterforms onto the marble before inscribing them. A change in weight of their strokes from vertical to horizontal carried over into the carved letterforms.

Fig 1.1.5 Phoenician to Roman

Phoenician letter A developed over a period of time within 1000 BCE Greek letter A takes from Phoenicia but flipped, and then eventually flips it again ninety degrees until we got the letter A that we have come to know today Roman letter A is the more refined version based on the brush that is being used

2. Hand script from 3rd - 10th century C.E.

Square Capitals: Written version of letterforms found in Roman monuments. These letterforms have serifs added at the end of the main stokes. They started to use reap ends with a broader edge and a slant to the tool being used. As a result, the thick strokes that have developed and added the serifs

Fig 1.1.6 Square Capitals (4th or 5th century)

Rustic Capitals: A compressed version of square capitals. These letterforms allowed for twice as many words on a sheet of parchment. Faster and easier to write, but harder to read.

Fig 1.1.7 Rustic Capitals (late 3rd - mid 4th century)

Roman Cursive: Square and rustic capitals were reserved for important documents. Everyday transactions were written in cursive hand, where forms were simplified for speed. Roman Cursive was the beginning of lowercase letterforms.

Fig 1.1.8 Roman Cursive (4th century)

Uncials: Incorporated some aspects of Roman cursive hand, especially with A, D, E, H, M, U and Q. Uncials are small letters. Their broad forms are more readable at small sizes than rustic capitals.

Uncials didn't have lowercase and uppercase - they have elements of capital and lowercase integrated into the writing system

Fig 1.1.9 Uncials (4th - 5th century)

Half-uncials: Further formalization of the cursive hand. The start of lowercase letterforms, with the use of ascenders and descenders. Development of the capital letters C → condensed rustic capitals → script form of capital letters → develops the first type of lowercase letter forms → introduction of a formal lowercase letter form

Fig 1.1.10 Half-uncials (C. 500)

Charlemagne, the first unifier of Europe since the Romans, entrusted Alcuin of York, Abbot of St Martin of Tours to standardize all ecclesiastical texts. A standardized writing system would convey messages more accurately and precisely. The monks rewrote the texts introducing majuscules (uppercase), minuscule (lowercase), capitalization, and punctuation.

Fig 1.1.11 Caloline minuscule (C. 925)

3. Blackletter to Gutenberg’s type With the dissolution of Charlemagne’s empire came regional variations upon Alcuin’s script. They developed their personal styles (impacted by geography, nature, characteristics, and tools) Blackletter/Textura: A condensed strongly vertical letterform, popular in northern Europe Rotunda: A rounder more open-hand letterform, popular in the south

Fig 1.1.12 Blackletter (C. 1300)

Gutenberg marshaled them all to build pages that accurately mimicked the work of the scribe’s hand – Blackletter of northern Europe. The process of writing takes a long period of time, thus not many books can be created and they were costly. Gutenberg developed a mechanism where printing/documenting can be done much more quickly. His type mold required a different brass matrix, or negative impression, for each letterform. They could print many pages and produce more books than a scribe could. He chose to produce the Bible in this highly productive way.

Fig 1.1.13 42-Line Bible (C. 1455)

4. Text type classification

Fig 1.1.14 Text type classifications

1450 Blackletter⟶ 1475 Old style⟶ 1500 Italic ⟶ 1550 Script ⟶1750 Transitional ⟶ 1775 Modern ⟶ 1825 Square Serif/ Slab Serif⟶ 1990 Serif/ Sans Serif

Lecture 2: Text Pt.1

1. Kerning and Letterspacing

Kerning: The automatic adjustment of space between letters.

Letterspacing: To add space between the letters.

Tracking: The addition and removal of space in a word or sentence.

Fig 1.2.1 Kerning and Letterspacing

Diagram on the left is when you have the letters in their own space. Diagram on the right is when you kern the space between the letters ‘Y’ and ‘e’, hence the ‘e’ seems to invade the space of the letter ‘Y’.

Tracking

The addition and removal of space in a word or sentence. When you letter space and kern in one word or sentence, ‘Y’ and ‘E’, it is referred to as tracking.

The looser the tracking, the harder it is to read the text.

Normal tracking is easy to read

Loose tracking and tight tracking are harder to read because the pattern that produced the words is less readable and recognizable

Letterspacing

Uppercase letters are always letter spaced as they are able to stand on their own.

Lowercase letters require the counterform* between letters to be readable

*Counterform: The black spaces between the white letters. Adding letter spacing breaks the counterform, thus reducing the readability of that particular word or sentence

2. Formatting text

Gray value: Text on a white page. The value of the entire text on a white page.

If the grayness is too dark, there is not enough leading or you've given kerning to the text, thus it becomes dark. If the gray text is too light, there is too much letter spacing or you give it too much leading (the space between each line of text).

Flush left: Closely mirrors the asymmetrical experience of handwriting. Each line starts at the same point but ends wherever the last word on the line ends. Spaces between words are consistent throughout the text, which creates an even gray value. However, this format creates ragging (a jagged shape endpoint) on the right.

Centered: Imposes symmetry on the text, giving value and weight to both ends of any line. It transforms fields of text into shapes, which adds a pictorial quality. Centered type creates such a strong shape on the page, it is important to amend line breaks so that the text does not appear too jagged.

Flush right: Emphasizes the end of a line as opposed to its start. It can be useful in situations (like captions) where the relationship between text and image might be ambiguous without a strong orientation to the right. However, this format creates ragging on the left.

Justified: Imposes symmetrical shape on the text. It is achieved by expanding or reducing spaces between words and letters. The result of the openness of lines can occasionally produce ‘rivers’ of white space (gaps between the words) running vertically through the text. Careful attention to line breaks and hyphens is required to amend this problem.

3. Texture

Type that calls attention to itself before the reader can get to the actual words should be avoided. If you see the type before you see the words, change the type. A type with a relatively generous x-height or relatively heavy stroke width produces a darker mass on the page than a type with a relatively smaller x-height or lighter stroke. Sensitivity to these differences in color is fundamental for creating successful layouts.

There is more readability if the x-height is larger than the ascender (space above) and descender (space below).

Different typefaces have different gray values, some are lighter and some darker. A typeface with a middle gray value is the best choice (e.g. Baskerville, Bembo, Garamond)

4. Leading and Line Length

Type size: Text type should be large enough to be read easily at arm's length. Leading: The space between adjacent lines of the typeface. Text that is set too tightly encourages vertical eye movement; a reader can easily lose track. Type that is set too loosely creates striped patterns that cause distraction. Line Length: Shorter lines require less leading; longer lines more. Keep the line length between 55-65 characters. Extremely long or short line lengths impair reading.

5. Type Specimen Book

A type specimen book shows samples of typefaces in various different sizes. It provides an accurate reference for type, type size, type leading, type line length, etc.

Compositional requirement: Text should create a field that can occupy a page or a screen. An ideal text should have a middle gray value. It is useful to enlarge the type to 400% on the screen to get a clear sense of the relationship between descenders on one line and ascenders on the line below. If the outcome is on a printed page, it is best to print out an actual page to look closely at the details. If its outcome is on screen, then the judging type on screen is accurate.

Lecture 3: Text Pt.2

6. Indicating Paragraphs

There are several options for indicating paragraphs:

The ‘Pilcrow’ (¶)

Pilcrow: A holdover from medieval manuscripts seldom use today. It is one of the hidden characters or blue indicators that help in formatting large amounts of text.

Line space (leading*)

Paragraph space should be the same as the line space to ensure cross alignment across columns of text. E.g. If the line space is 12pt, then the paragraph space is 12pt. Line space: The space from the baseline of a sentence to the descender of the next sentence. Leading: The space between each line of text. As design students, we should use the name leading in typography. Cross alignment: When you have two columns of text sitting next to each other, the text line is aligned with the text line on the next column

Indentation

Standard indentation: Indent is the same size of the line spacing or the same as the point size of the text.

Extended paragraphs

Extended paragraphs: Create unusually wide columns of text.

7. Widows and Orphans

Widow: Short line of the type left alone at the end of a column of text.

Avoided by creating a force line break - rebreak your line endings throughout your paragraph so that the last line of any paragraph is not noticeably short.

Bringing down another word - adjusting the tracking of the line before letting the last word in the second last line moves down to the last line.

Orphan: Short line of the type left alone at the start of a new column.

Avoided by adjusting the length/width of the column. Make sure that no column starts with the last line of the preceding paragraph

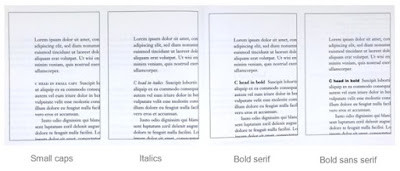

8. Highlighting Text

You can highlight text with different methods

Use the same typeface with Italics, Bold, or change color of the text (black, cyan, magenta, yellow only)

Use bold with different type families - from serif to sans serif for that text

- Note: sans serif font is usually larger than a serif font in the same point size. In this example, the sans serif font (Univers) has been reduced by 0.5 pt to match the x-height of the serif typeface.

Place a field of colour at the back of the text

Place typographic elements, such as bullet points

Use quotation marks

- Quotation marks, like bullets, can create a clear indent, breaking the left reading axis. Compare the indented quote at the top with the extended quote at the bottom.

- Prime is not a quote. The prime is an abbreviation for inches and feet. (The top quotation marks that are straight in the picture)

9. Headline within Text

There are many kinds of subdivisions within the text of a chapter. The following visuals have been labeled (A, B and C) according to the level of importance. A head: indicates a clear break between the topics within a section. In the following examples, the ‘A’ heads are set larger than the text, in small caps and in bold. The fourth example shows an A head ‘extended’ to the left of the text.

B heads: are subordinate to A heads. B heads indicate a new supporting argument or example for the topic at hand. As such they should not interrupt the text as strongly as A heads do. Here, the B heads are shown in small caps, italic, bold serif, and bold san serif.

C head: highlight specific facets of material within B head text. They don't interrupt the flow of reading. As with B heads, these C heads are shown in small caps, italics, serif bold, and sans serif bold. C heads in this configuration are followed by at least an em space (two space bar presses) for visual separation.

10. Cross Alignment

Cross-aligning headlines and captions with text type reinforces the architectural sense of the page—the structure—while articulating the complimentary vertical rhythms. Cross-align can be maintained by doubling the leading space of the text type.

When you have different bodies of text and there are different point sizes, it's very hard to maintain cross-alignment. However, if the difference in point size is not large, you will be able to maintain cross-alignment by doubling the leading space.

For example, if a paragraph of text is 13pts, you can double the bigger font sizes (headline) of the other column to 26 pts. Despite the discrepancy, because it's a doubling of the leading, the cross-alignment of the text will always remain.

In this example, one line of headline type cross-aligns with two lines of text type, and (right; bottom left) four lines of headline type cross-align with five lines of text type.

Lecture 4: Basic

1. Describing Letterforms

Fig 1.4.1 Letterforms - PDF

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NLJv0sp4THLXwVSl0YTwZF5fBZSm8JNi/preview

2. The Font

Uppercase and Lowercase

Small Capitals: Uppercase letterforms drawn to the x-height of the typeface.

Uppercase Numerals (lining figures): Same height as uppercase letters and set to the same kerning width. They are most used with tabular material and uppercase letters.

Lowercase Numerals: Set to x-height with ascenders and descenders. Best used when using upper and lowercase letterforms.

Italic: Refer back to 15th-century Italian cursive handwriting. Oblique is typically based on the roman form of the typeface.

Punctuation, miscellaneous characters: Miscellaneous characters can change from typeface to typeface. It’s important to ensure that all the characters are available in a typeface before choosing the appropriate type.

Ornaments: Ornaments Used as flourishes in invitations or certificates. They usually are provided as a font in a larger typeface family. Only a few traditional or classical typefaces contain ornamental fonts as part of the entire typeface family (Adobe Caslon Pro).

3. Describing Typefaces

Roman: Uppercase forms are derived from inscriptions of Roman monuments. A slightly lighter stroke in roman is known as ‘Book’.

Italic: Named for 15th-century Italian handwriting on which the forms are based. Oblique conversely is based on the roman form of the typeface.

Boldface: Characterized by a thicker stroke than a roman form. It can also be called ‘semibold’, ‘medium’, ‘black’, ‘extra bold’, or super.

Light: A lighter stroke than the roman form. Even lighter strokes are called ‘thin’.

Condense: A version of the roman form, and extremely condensed styles are often called ‘compressed’.

Extended: An extended variation of a roman font.

4. Comparing Typefaces

Differences in x-height, line weight, forms, stroke widths, and in feeling. For any typographer, these feelings connote specific use and expression. Each typeface gives different feelings, it is important for us to understand these typefaces well and see the appropriateness of type choices.

The Rs display a range of attitudes, some whimsical, some stately, some mechanical, others calligraphic some harmonious, and some awkward.

Lecture 5: Understanding

1. Understanding Letterforms

Uppercase 'A' (Baskerville & Univers)

The uppercase letterforms suggest symmetry, but it is not actually symmetrical. Both Baskerville and Univers demonstrate the meticulous care a type designer takes to create letterforms that are both internally harmonious and individually expressive. Baskerville: Two different stroke weights of the Baskerville stroke form; each bracket connecting the serif to the stem has a unique arc Univers: The width of the left slope is thinner than the right stroke

Lowercase 'a' (Helvetica vs Univers)

The complexity of each individual letterform is neatly demonstrated by examining the lowercase ‘a’ of two seemingly similar sans-serif typefaces—Helvetica and Univers. A comparison of how the stems of the letterforms finish and how the bowls meet the stems quickly reveals the palpable difference in character between the two.

2. Maintaining x-height

X-height generally describes the size of the lowercase letterforms. Curved strokes, such as in ‘s’, must rise above the median (or sink below the baseline) in order to appear to be the same size as the vertical and horizontal strokes they adjoin.

3. Form / Counterform

Counterform (or counter)—the space describes, and is often contained, by the strokes of the form. When letters are joined to form words, the counterform includes the spaces between them. How well are the counters handled when you set the type determines how well the words hang together - how easily we can read what’s been set. Counterform has the same importance as the letterforms as it helps to recognize the shape of the letters and assure the readability of the words.

We could examine the counterform of letters by enlarging each letter and analyzing them. It gives us a glimpse into the process of letter-making.

Its worth noting here that the sense of the ‘S’ holds at each stage of enlargement, while the ‘g’ tends to lose its identity, as individual elements are examined without the context of the entire letterform.

4. Contrast

The basic principles of Graphic Design is also applied in typography. The simple contrasts produce numerous variations: small+organic / large+machines; small+dark / large+light, etc.

Lecture 6: Screen & Print

Typography in Different Medium

In the past, typography was viewed as living only when it reached paper. Nothing changed once a publication was edited, typeset, and printed. Today, typography exists not only on paper but on a multitude of screens. It is subject to many unknown and fluctuating parameters, such as the operating system, system fonts, the device and screen itself, the viewport, and more. Our experience of typography today changes based on how the page is rendered, because typesetting happens in the browser.

Print Type vs Screen Type

1. Type for Print

The type was designed intended for reading from print long before we read from the screen. Designers should ensure the text is smooth, flowing, and pleasant to read. Common typefaces for print: Caslon, Garamond, Baskerville, Univers (elegant, intellectual, highly readable at small font size)

2. Type for Screen

Typefaces intended for use on the web are optimized and often modified to enhance readability and performance onscreen in a variety of digital environments. This can include a taller x-height (or reduced ascenders and descenders), wider letterforms, more open counters, heavier thin strokes and serifs, reduced stroke contrast, modified curves and angles, etc.

Another important adjustment – especially for typefaces intended for smaller sizes – is more open spacing. All of these factors were made to improve character recognition and overall readability in the non-print environment (web, e-books, e-readers, and mobile devices)

3. Hyperactive Link/ Hyperlink

A hyperlink is a word, phrase, or image that you can click on to jump to a new document or a new section within the current document. Hyperlinks are found on nearly all Web pages, allowing users to click their way from one page to another. Text hyperlinks are normally blue and underlined by default.

4. Font Size for Screen

16-pixel text on a screen is about the same size as text printed in a book or magazine; this is accounting for reading distance. Printed text is typically set at about 10 points because we read books pretty close — only a few inches away . If you were to read them at arm’s length, you’d want at least 12 points, which is about the same size as 16 pixels on most screens

5. System Fonts for Screen/Web Safe Fonts:

Each device comes with its own pre-installed font selection, which is based largely on its operating system. Windows, macOS, and Google's own Android system have their own system fonts. Web-safe fonts appear across all operating systems. They are a small collection of fonts that overlap from Windows to Mac to Google.

E.g. Open Sans, Lato, Arial, Times New Roman, Times, Courier New, Courier, Verdana, Georgia, Palatino, Garamond

6. Pixel Differential Between Devices

The screens used by our PCs, tablets, phones, and TVs are not only different sizes, but the text you see on-screen differs in proportion too, because they have different-sized pixels. Even within a single device class, there will be a lot of variation

Static vs Motion

1. Static Typography

Static typography has minimal characteristics in expressing words. Traditional characteristics such as bold and italic offer only a fraction of the expressive potential of dynamic properties. E.g. billboards, posters, magazines, and fliers. Whether they are informational, promotional, formal, or aspirational pieces of designs, the level of impression and impact they leave on the audience is closely knitted to their emotional connection with the viewers.

2. Motion Typography

Temporal media offer typographers opportunities to “dramatize” type, for letterforms to become “fluid” and “kinetic”. Film title credits present typographic information over time, often bringing it to life through animation. Motion graphics, particularly the brand identities of film and television production companies, increasingly contain animated type. Type is often overlaid onto music videos and advertisements, often set in motion following the rhythm of a soundtrack. On-screen typography has developed to become expressive, helping to establish the tone of associated content or express a set of brand values. In title sequences, typography must prepare the audience for the film by evoking a certain mood.

Fig 1.6.6 Motion Typography in "Se7en" (1995) title credits

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Fa_8v8rFlQ2C5sBRt7drwWp8NZxm1CfD/preview

TASK 1: Exercise 1 - Type Expression

For Exercise 1, we were given six words to make type expressions of. The words are Rain, Fire, Crush, Water, Dissipate, Freedom, and Sick. No graphical elements or distortions are allowed and we are limited to only 10 typefaces.

1. Sketches

These are my type expression sketches. We are required to choose four words and create 3 type expressions for each. I chose the words Freedom, Dissipate, Rain, Crush, and Water (it was recommended to choose an additional word in case one got rejected). My favorites for each word would be freedom #1 and #2, dissipate #1 and #3, crush #1, rain #2, and water #2.

2. Digitization

During the digitization process, I experimented with different designs and typefaces to create the word expression. There are numerous rough digitizing attempts, before arriving at the final design. This is my process for the design of each word.

FREEDOM

In my process of digitizing “Freedom”, I went through 5 designs before getting the look I desired.

I made the letters look as if they were breaking free from the word itself. I played around with the different typefaces provided and changed to Gills Sans Std. In attempts #2 and #3, I used character rotation for the letter “E”. To create the breaking apart look in attempt #4, I used the knife tool (which I remembered from Mr. Vinod’s demonstration in the Week 2 lesson). I combined the use of the knife tool and the rotation of letters for my final design.

DISSIPATE

I had a clear idea of how I wanted to digitize “Dissipate”. I played around with the typefaces, font style color, and leading. For the final, I used ITC Garamond Std with the words getting smaller and lighter in color, with increasing leading.

CRUSH

My first attempt at digitizing “Crush” was done with Gill Sans Std, but I stretched the letters “R”, “U”, “S”, and “H”, which was not allowed. This also altered the vertical and horizontal scale - it should be at 100%. I tried to change the leading between letters and the font style of each letter instead but to no avail. After multiple attempts to achieve the look of my sketch, I ultimately decided to change the design. I am much happier with how it looks now. The word “Crush” is getting crushed by a bigger “Crush”. I used a lighter font style for the word getting crushed, and increased the size and used a bold font style for the other.

RAIN

During Mr. Vinod’s feedback on my type expression sketches, he shared a very smart suggestion. To create the umbrella shape, I could use the bracket symbols. He also pointed out how the lowercase “i” could look like raindrops. I applied his feedback and suggestions to my digitization. I used an uppercase “I” to make a full umbrella, and a lowercase “i” to create the rain. I found out that changing the typeface of the bracket symbol gave me different umbrella shapes. In the final, I used ITC Garamond for the umbrella, and Futura Std for the word.

Following the feedback given in the Week 3 class, I reworked my type expressions digitization.

1. Freedom: I changed the whole design to express the meaning of freedom and independence. It looks better now and makes more sense than my original idea of breaking apart. 2. Rain: I made the raindrops smaller using a lighter font style to make them look more like rain. 3. Dissipate: Something felt off with the design, so I changed the typeface and adjusted the spacing between the words. 4. Crush: There was nothing wrong with the design but I decided to make the words look even more crushed and used lowercase instead.

Final Type Expressions

Fig 2.9 Final Type Expression - JPEG, Week 3 (18/04/2023)

Fig 2.10 Final Type Expression - PDF, Week 3 (18/04/2023)

3. Animation

We are required to choose one word from the four final type expressions to be animated. Before starting our animation, we have to watch the animation tutorial video by Mr. Vinod. The video demonstrates how to make an animation using Illustrator and Photoshop. A useful tip was to think about how the word would look animated in each frame.

I chose to animate the word “Rain”. My idea was to animate a rain downpour.

This was my first attempt at animation. I followed the steps shown in the video to get a hand on animating the words.

My second attempt involved making the raindrops fall one at a time and gradually begin to get heavier. The movement, added with the rain splatter on the umbrella, is a lot more natural compared to my first attempt.

Fig 2.13 Animation timeline, Week 3 (22/04/2023)

I did a few adjustments and touch-ups to my animation before the final work.

Final Animated Type Expression

TASK 1: Exercise 2 - Text Formatting

For Exercise 2, we have to create one final layout of text formatting (i.e. type choice, type size kerning, leading, paragraph spacing, alignment, line length, etc.). This exercise will help us develop our skills with the appropriate software, Adobe InDesign, and our knowledge of information hierarchy and spatial arrangement.

.

1. Text Formatting Lecture 1: Kerning and Tracking

Kerning: adjusts the space between individual letterforms. You kern when there are awkward counter-spaces between the letterforms

Tracking (letter-spacing): adjusts spacing uniformly over a range of characters

Fig 3.4 Before and after changing the 'J' from Black to Bold, Week 4 (28/04/2023)

Fig 3.5 Before and after kerning the letters 'J’ and ‘O’, Week 4 (28/04/2023)

2. Text Formatting Lecture 2: Font Size, Line-Length, Leading & Paragraph Spacing

A good page layout is dependent on an attractive margin space. An equal margin space has no effect on the viewer. An unequal margin is attractive because the white space creates dynamism.

- Point size (for A4 or A3): 8 pt to 12 pt

- Line length: 55 to 65 characters

- Leading: +2 to 3 points of point size (depending on the typeface)

- Paragraph spacing: Same as leading

At a 9-point size → Check the number of characters in that row (55 to 65) → Set leading two points larger → Use the same unit as leading for paragraph spacing

3. Text Formatting Lecture 3: Alignment, Paragraph Spacing, Text Fields & Ragging

- Headings: Double the point size and leading of body text - Paragraph spacing: same as leading - Ensure same text width for the same text of information. If they are different widths, it is seen as separate pieces of information - Tracking and kerning: Do not exceed +3/-3 of tracking (Alt+arrow key) - Hyphenation: You can turn off hyphenation. If hyphenation is turned on, there can not be too many. - Flowing text from one column to another by linking with red plus - Use left align or left justify. Left alignment is preferred. - If there are lots of words, do not use the right alignment and central alignment - When using a justified alignment, the column space needs to be increased from 5mm to 7-10mm - If using justified, make sure there aren’t many rivers (large spaces between the words). You can adjust space using tracking/kerning

4. Text Formatting Lecture 4: Cross Alignment & Baseline Grid

- Maintain cross alignment

- Leading must be multiples of 2 for cross alignment - To achieve cross alignment you need to have the baseline grid turned on (View → Grids → Show Baseline Grid)

Layout

Fig 3.9 Layout Progress, Week 4 (30/04/2023)

These are the different layouts I did. I have chosen Layouts #1, 4, 8, 9, and 12 to choose from as the final.

As seen in the figure above, without tracking and kerning, there is lots of ragging. I used forced line breaks and kerning and tracking to reduce the ragging.

Layout #1

Fig 3.11 Layout #1, Week 4 (30/04/2023)

Fonts: ITC Garamond Std (Bold - Heading; Bold Italic - Byline), Gill Sans Std (Regular - Captions; Regular - Body Text) Point size: 10pt (body text), 9pt (captions), 28pt (headline), 11pt (byline) Leading: 12pt (body text), 11pt (captions), 30pt (headline) Paragraph spacing: 12pt (body text), 11pt (captions) Line length: 60 characters Alignment: Left align Columns: 4 Margins: 12.7mm (top, bottom, left, right) Gutter: 5mm

Layout #2

Fig 3.12 Layout #2, Week 4 (30/04/2023)

Fonts: Janson Text LT Std (Bold - Heading; Bold Italic - Byline; Bold Italic - Caption), Bembo (Regular - Body Text) Point size: 10pt (body text), 11pt (captions), 28pt (headline), 11pt (byline) Leading: 12pt (body text), 13pt (captions), 30pt (headline) Paragraph spacing: 12pt (body text), 13pt (captions) Line length: 60 characters Alignment: Left align Columns: 4 Margins: 12.7mm (top, bottom, left, right) Gutter: 5mm

Feedback from Week 5: Good layout. Could have a more interesting headline and byline style

Layout #3

Fig 3.13 Layout #3, Week 4 (30/04/2023)

Fonts: ITC Garamond Std (Bold - Heading; Bold Italic - Byline), Gill Sans Std (Regular - Captions; Regular - Body Text) Point size: 10pt (body text), 9pt (captions), 28pt (headline), 11pt (byline) Leading: 12pt (body text), 11pt (captions), 30pt (headline) Paragraph spacing: 12pt (body text), 11pt (captions) Line length: 60 characters Alignment: Left align Columns: 4 Margins: 12.7mm (top, bottom, left, right) Gutter: 5mm Feedback from Week 5: Interesting layout, but the spacing is too harsh and uneven.

Layout #4

Fig 3.14 Layout #4, Week 4 (30/04/2023)

Fonts: Janson Text LT Std (Bold - Heading; Bold Italic - Byline; Bold Italic - Caption), Bembo (Regular - Body Text) Point size: 10pt (body text), 11pt (captions), 28pt (headline), 11pt (byline) Leading: 12pt (body text), 13pt (captions), 30pt (headline) Paragraph spacing: 12pt (body text), 13pt (captions) Line length: 60 characters Alignment: Left align Columns: 4 Margins: 12.7mm (top, bottom, left, right) Gutter: 5mm Feedback from Week 5: Center align of the headline, byline, caption, and the picture is awkward. Everything is left aligned.

Fonts: Gill Sans Std (Bold - Heading; Bold Italic - Byline; Regular - Captions; Regular - Body Text) Point size: 10pt (body text), 10pt (captions), 28pt (headline), 11pt (byline) Leading: 12pt (body text), 12pt (captions), 30pt (headline) Paragraph spacing: 12pt (body text), 12pt (captions) Line length: 60 characters Alignment: Left align Columns: 4 Margins: 12.7mm (top, bottom, left, right) Gutter: 5mm After receiving the Week 5 feedback, I did a few adjustments and touch-ups to my text formatting before submitting my final work.

Final Text Formatting

Fig 3.17 Final Text Formatting with grids - JPEG, Week 5 (02/05/2023)

Fig 3.18 Final Text Formatting without grids - PDF, Week 5 (02/05/2023)

Fig 3.19 Final Text Formatting with grids - PDF, Week 5 (02/05/2023)

HEAD Fonts: Janson Text LT Std (Bold, Bold Italic - Heading; Roman - Byline) Point Size: 45pt, 40pt (headline), 16pt (byline) Leading: 34pt (headline), 13pt (byline) Paragraph spacing: - BODY Fonts: ITC New Baskerville Std (Roman - Body Text; Roman - Caption) Point Size: 9pt (body text), 8pt (captions) Leading: 11pt (body text), 11pt (captions) Paragraph spacing: 11pt (body text) Line length: 57 characters Alignment: Left align Columns: 4 Margins: 12.7mm (top, bottom, left, right) Gutter: 5mm

WEEK 2

General feedback

Do sketches before digitizing, it is important to explore ideas. Use minor graphical elements and no/little distortions. Take into context the typefaces provided.

Specific feedback

1. Are the explorations sufficient?

Not really. Most of my sketches were similar to my classmates. While this is expected, and people can have similar ideas, I should explore more ideas to improve them.

2. Does the expression match the meaning of the word?

Yes

3. On a scale of 1–5, how strong is the idea?

On a scale of 1-5, I would give myself a 3 for the ideas.

4. How can the work be improved?

Mr. Vinod’s advice was to play around with the counter space, and different characters. E.g. using the bracket () symbol to create an umbrella shape

The words ‘Rain’ and ‘Water’ are too graphical. On a scale of 1-5, I would give myself a 3 for the ideas. A lot of my ideas are similar to others, nothing wrong with that. A suggestion he gave me for my idea on ‘Rain #2’, is to use different letters to create the shape of the umbrella; basically skirting around the rules. For ‘Crush #1’, I could use different typefaces and sizes when digitizing the word.

WEEK 3

General feedback

Consider the overall composition, as well as how much space the word uses in the square. Use the right font to express the word.

Specific feedback

1. Do the expressions match the meaning of the words?

Yes

2. Are the expression well crafted (crafting/lines/shapes)?

Yes

2a. Do they sit well on the art-board

Yes, they sit relatively well

2b. Are the composition engaging? Impactful?

They could be more impactful

3. Are there unnecessary non-objective elements present?

Yes, there are some unnecessary elements

4. How can the work be improved?

Change the typefaces, try different font sizes

Use different font sizes and depths for the raindrops in “Rain”. Change the typeface to better fit the word, in this case, “Dissipate”. Mind the spacing between the words in “Dissipate” The word expression of “Freedom” does not make sense, change the design of the word.

WEEK 4

General feedback

When you create an animation, it is recommended to pause at the last frame to give the last frame a couple of seconds before the animation started again. Use an off-white background for the blog to make sure figures can be seen.

Specific feedback

Can proceed with the GIF

WEEK 5

General feedback

Be mindful of spacing between the headline and byline. If left aligned, the column space should be 5mm; if left justified, make it 7mm. Downsize the font size of the abbreviation with capitals. Choose an image that is relevant to the text.

Specific feedback

1. Is kerning and tracking appropriately done?

Yes

2. Does the font size correspond to the line-length, leading & paragraph spacing

Yes

3. Is the alignment choice conducive to reading?

Yes

4. Has the ragging been controlled well?

No, could be improved

5. Has cross-alignment been established using base-line grids?

Yes

6. Are widows and orphans present?

No

Fix the ragging by switching hyphenations on and off. Spacing for some layouts are too harsh. Can use a more interesting headline design for Layout #2.

Experience

This exercise has taught me a lot about typography throughout the last five weeks. We completed Task 1 bit by bit and received feedback from Mr. Vinod each week to make changes and improvements. We also reviewed our peer’s work, which helped me learn from their ideas and feedback from Mr. Vinod. It was a little difficult for me to come up with ideas during the sketching stage as we could not use any graphical elements. Coming up with original ideas was one of the obstacles for both exercises because I knew my ideas would be similar to those of my classmates. It was also challenging to use Adobe Illustrator during the digitizing of our work. It is new software for me and most of my classmates. There are lots of restrictions during this exercise but I am grateful for it. It has taught me how to work within constraints, think outside of the box, the importance of formatting text, and how typography is an art form as much as painting, drawing, etc.

Observations

I observed that I have learned better when I received feedback every week. By staying on progress every week, I am able to get full guidance and the necessary feedback to improve my work. I noticed that when I follow the lecture and do my work at the same time, I am able to retain the information more effectively. I enjoy the chance to pick up new knowledge and skills and learn more about Adobe Illustrator and InDesign. Watching the lecture videos have helped me to learn more about the theory side of typography, and practical demonstrations through the physical lectures. All this has helped me to expand the knowledge I have about typography and its basics such as kerning, line and paragraph spacing, tracking, cross alignment, etc.

Findings

I found that my sketches and ideation stage need improving as I am unable to convey my ideas effectively onto the page. Knowing this, I will need to practice coming up with more unique ideas. I also found that typography has many rules and terminology to understand and remember. Typography is an art of organizing letters and/or words in the way they develop meaning, become readable, and look appealing. To become better in typography, we must pay close attention to even the smallest of details. There are several things to consider (font, kerning, leading, tracking, typeface, etc.) to make the design of the text good.

Fig 4.1 "Typographic Design: Form and Communication" Book

Based on the list of recommended readings, I did some further reading on "Typographic Design: Form and Communication". History is one of my favorite subjects, so I decided to start reading the chapter entitled “The Evolution of Typography”. Chapter 1: The Evolution of Typography

Fig 4.2 Chapter 1: The Evolution of Typography (3150 BCE–1450 CE), Page 2

The origins of writing to Gutenberg’s invention of movable type: This book is filled with visual images that showcase the development of type, from beginning to end, and how style changes as time progresses. The earliest written documents were inscriptions impressed on clay tablets. Early writing systems including cuneiform and hieroglyphics were the precursors of the modern alphabets.

Fig 4.3 Chapter 1: The Evolution of Typography (1800-1899 CE), Page 17

19th century and the Industrial Revolution: The growth of industrialization came with the development of new technologies and techniques for printing. One of the most significant development was the Linotupe machine which allowed for faster typesetting. This revolutionized the printing industry and paved the way for mass production of printed materials. In the 19th century, the typefaces became graphical, larger, and bolder in lettering and shading.

Fig 4.4 Chapter 1: The Evolution of Typography (2000 CE), Page 27

The start of the new century saw typography evolving rapidly due to the advancements in digital technology. The introduction of web fonts and desktop publishing software allowed designers to experiment further. Designers also had to consider how type would appear at different sizes, resolutions, and screens. This led to new typefaces being developed specifically for on-screen reading.

Chapter 2: The Anatomy of Typography

The chapter is about the basic elements of letterforms, such as the stem, ascender, descender, bowl, serif, and counter. These elements come together to form individual letters and discuss the differences between uppercase and lowercase letters.

Fig 4.6 Chapter 2: The Anatomy of Typography, Page 39

The classification of typefaces is covered in the next section, including serif, sans-serif, script, display, and monospaced types. It describes the distinctive qualities of each category and provides examples of well-known typefaces from each classification. For example, the sans serif typefaces have uniform strokes, little to no contrast between thick and thin strokes, and are geometric. Some of the most popular sans serif typefaces include Helvetica, Futura, and Serifa.

Fig 4.7 Chapter 2: The Anatomy of Typography, Page 43

The designer measures and determines the spacing between typographic elements in addition to the type. Traditionally, metal blocks, known as quads, were inserted between the pieces of type to achieve the interletter and interword space.

Fig 4.8 Chapter 2: The Anatomy of Typography, Page 47

The Univers Family: When all the major characteristics - weight, proportion, and angle - are in a united family, we get a full range of typographic contrast. The Univers family uses numerals to designate the typefaces. All the designs are developed from Univers 55, which is ideal for text settings. The first digit in each font’s number indicates the stroke weight, and the second number indicates the expansion and contraction of the spaces between the letters. The chapter also discusses typographic alignment, including left-aligned, right-aligned, centered, and justified text, and discusses the impact of alignment on readability and the overall visual rhythm of the design. Point size, leading (line spacing), kerning (letter spacing), and tracking affect the readability and visual harmony of the typography. All this was already covered in Mr. Vinod’s lecture videos.

.png)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment